I have lived in Austin for over 15 years and I am a home owner, dad and entrepreneur. My wife and I have raised two kids here and love Austin. However, I am still processing the events of February 2021, including the collapse of our deregulated energy infrastructure, the lack of preparedness by city, county and state agencies to respond quickly and effectively to the snowballing disaster and the ongoing trauma, stress and displacement being experienced by thousands of my fellow Austinites.

One of the major areas of fragility in our city is our food system. I would like to share my thoughts on this, but first some background. I am a 25+ year veteran of the food industry and I have a unique perspective on this subject. My experiences include local and regional food procurement and retail operations in New York, Florida, Texas and elsewhere, various food service and farmer’s market gigs, and seven years leading the national Grocery division at Whole Foods. In this role, I led a team that grew grocery/center store sales to over $5 Billion annually and I was immersed in supply chains, assortment planning, category management, product development, private label/store brands, and negotiating wholesale agreements, including a multi-year, multi-billion dollar contract with our national wholesale partner. I left Whole Foods in 2016 and have spent the last 5 years as a board member, advisor, founder and partner in service to over 20 natural products retail, packaged food enterprises, NGOs and community groups, including Farmshare Austin and the Austin Travis Food Policy Board. For further info, please see my LinkedIn profile.

As context, the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated already existing food inequities in Austin that are largely along lines of race, class and geography. Over 25% of Austin households are food insecure according to recent data, with numbers even higher among children. This means that thousands of adults and children in our metro area regularly miss meals or have few options for a healthy diet. I think it is insane in a city with so many billionaires and successful entrepreneurs that we are letting our neighbors go to bed hungry and malnourished. What kind of city are we?

Austin’s history of segregation and racist urban development policies have created a food system that prioritizes innovation and availability in wealthier, white neighborhoods, while many middle and lower income neighborhoods, primarily Black and Hispanic/Latin, have fewer choices and lower quality options. My frequent comparative shops of grocery stores in Southeast Austin and North Austin versus Westlake Hills or Circle C provides ample evidence of this food apartheid. And that is on a good day. Covid-19 has brought with it a huge increase food bank traffic, radically different shopping patterns that have strained supply chains and forced retailers to slim down offerings and focus on staying in stock. The additional shock of winter storm Uri in February emptied grocery shelves pretty quickly across the city, with many retail chains and wholesalers taking weeks to fully recover their inventory par levels and preferred assortments. Many friends and neighbors ran out of food and waited in line for hours at grocery stores during and after the storm.

Austin is wholly dependent on the private sector for our food supply, primarily in terms of retail, wholesale, small scale processing, food service and charitable sectors. There is yet to be an inclusion of policies such as food security, food access or food sovereignty in emergency management planning. Despite Austin’s global reputation as a progressive foodie destination, food is not a common good for our residents, but is treated as a commodity for those with access and resources, or as a charity for those without. This is a major shortcoming of framing food as a private good.

The private sector does many things well. Grocers carry an astounding array of products, including many organic, sustainable and locally grown foods. They have been able to cater to tastes and trends of all demographic groups, from fifth generation Texans to recent immigrants to folks with food allergies and any combination of the above. Grocers provide great coupons, ads and promotional deals and have integrated online ordering, pickup and delivery while trying to keep customers and employees safe during the pandemic. They have been a huge provider of Covid-19 vaccines and health resources, in the absence of a truly functional public health system or universal medicare. They are our charitable neighbors and community members that we couldn’t imagine living without.

Yet these activities are all part of part of their business models and competitive strategies and are wholly dependent on market conditions. Are they able to compete on price, quality, assortment? Can they attract and retain a labor force that is compensated and treated fairly? Can they manage their supply chains and vendor relationships and stay in stock on what customers want? Recent crises have shown the vulnerability of most private sector supply chains and retail outlets, with most enterprises experiencing out of stocks, assortment changes, price inflation and quality issues. Food banks and food access NGO’s have picked up considerable slack during the pandemic, but they are also dependent on private sector enterprises further upstream for donations, such as food manufacturers and distributors, as well as national partners such as Feeding America, who redistribute goods from the private sector.

It’s important to note that food retailers run off of razor thin profit margins. Most retailers net out 1-2 cents of profit for every dollar of revenue. Their operations, procurement and supply chain, pricing strategy and expense management are all geared towards managing this bottom line, while not losing ground on their topline revenue or market share. The Austin retail market is one of the most competitive in the country. HEB-Central Market, Costco, Wal-Mart/Sam’s, Target and Amazon-Whole Foods dominate the market and a handful of other national chains such as Randall’s (Safeway/Albertson’s), Sprouts, Trader Joe’s, Natural Grocers compete for market share with Asian and Hispanic grocers such as Fiesta, 99 Ranch and H-Mart, as well as convenience stores and locally and family owned chains. We even have the only retail cooperative grocer in Texas, the venerable Wheatsville Coop, of which I am a long term member, but they are less than 1% of the retail market share. These chains put all of their efforts into retaining customers, growing their sales base, updating and refining their product assortment, managing their supplier relationships, navigating E-commerce fulfillment and delivery and of course, surviving the challenges associated with Covid-19. Larger retailers are also notorious for cutting deals with big food manufacturers to guarantee them shelf space in return for additional revenue, a practice that causes concentration of ownership in the food system, pushed junk food and highly processed ingredients and hurts smaller, more innovative companies that don’t have deep pockets.

The pandemic has caused a spike in sales for many large chains, but industry analysts, including myself, predict that many stores will see sales declines in the coming months as customers change spending habits, vaccinations increase and restrictions continue to relax. And all of these retailers are completely dependent on transactional relationships with their customers. Folks need to spend money to keep these businesses going, with the occasional exception, and there is no such thing as the right to food for those who need it. This is why SNAP is among the largest and most important food access initiatives in the world, because it enables people to spend money on food and generates further economic activity. However, private sector retailers are not public utilities, no matter how much we’ve grown accustomed to depending on them for basic needs.

All retailers are dependent on another, less visible portion of the supply chain that I’ve mentioned, called wholesale. Much wholesale distribution is now vertically integrated by large chains, but there are a number of large national and regional wholesalers that service these retail chains, including United Natural Foods, KeHe, McLane, Brother’s Produce and more. The profit margins on wholesale are even slimmer than retail and their supply chains are focused on efficiency and productivity, including “just-in-time” inventory. That is why I refer to them as wholesalers, not warehouses, since their business model is built on managing inventory turnover, concatenating the optimal mix for their retail customers based on what turns the quickest at the best profit margin, calculating how many pennies can be squeezed out of each warehouse slot and how much additional revenue can be extracted from suppliers through various marketing and ad vehicles through rebates and chargebacks that are invisible to consumers. This business model is a major reason why Covid-19 and Uri created large scale out of stocks and empty shelves across the city for days and weeks on end. There is no backstop or “safety stock” when the bottom line is at stake.

This reliance on the private sector creates a great deal of fragility in the local food system. Yet our food supply during a crisis is completely dependent on these enterprises. Frankly, this is terrifying and should give city officials pause given recent events. As someone who has been immersed in this world for many years, I feel it is irresponsible of the City of Austin to not have an emergency food plan that is independent of the profit-driven business models of private sector retailers and wholesalers, and takes pressure off of the donation-dependent food banks and food hubs that have been carrying more than their fair share of the food security burden.

I want to frame the rest of this discussion in terms of creating a public sector food commons for Austin. A commons is a regulated institution that is accountable to and shared by the people for their mutual benefit. (Please see works by Nobel Prize winner Elinor Ostrom or researcher Jose Vivero Pol for further background on the commons in the modern world, and the scholarly dismantling of white supremacist Garrett Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons” mythology. For more background on food utilities see more from John Ikerd. )

This concept of the commons would mean that food become a public good, with a sector of the food system committed to ensuring that this most basic human need is guaranteed to all who need it. Food should be a human right, especially good food that is nutritious, culturally relevant and ethically produced. We can start to address this on a municipal level, with the following suggestions as a starting point for building public sector food infrastructure that is resistant to crises and shocks in the supply chain.

Create a public sector emergency food utility:

Austin should look into leasing warehouse space in several industrial areas (or in multiple postal codes) around the metro area in order to procure, build and manage inventory of ambient grocery products for emergency food distribution, in case of weather, public health, ecological or other crises. This inventory should cover multiple product categories that could be stored at room temperature, has long shelf life and shelf stability, and should be culturally relevant and appropriate to Austin’s diverse populations. The shelf stable or “center store” departments of most grocery chains comprise more than half of their sales, so there are many product categories to cover, including water, juices and beverages, rice and grains, dried beans and legumes, canned/aseptic packaged soups, beans, vegetables, meals and entrees, bagged and boxed snacks, nuts and dried fruit, condiments and sauces, pasta and noodles, tofu and plant-based meat analogues, protein bars, powders and other nutritional supplements, and many more.

The goal here would be to carry and rotate enough inventory at each of these sites to support the caloric and nutritional needs for thousands of local residents in a culturally appropriate manner for at least a month, when and if a given crisis arises again. The inventory should be managed down and reordered as it codes out, and either donated or sold at or below cost to local partners that would handle the public or retail interactions, including food banks, food access NGO’s (such as Texas Center for Local Food, Farmshare Austin, Common Market or Dell Medical), public cafeterias (see below), community food activists, locally owned grocery or convenience stores or discount food outlets. By buying a limited number of items per category in volume, logistics costs could also be kept down.

While I don’t believe the city should be in a direct retail relationship with residents, since that would add significant operational costs and complexity, my friend Brahm Ahmadi of Community Foods Market in Oakland has suggested otherwise, “Public sector ownership could solve a problem that grocers serving lower-income communities are faced with: Providing low prices and high wages while also covering operating costs and producing net operating profit. Public sector ownership could reduce pressures to produce net profits, or even to break even. The gap between revenue and operating expenses could be funded out of the city budget. The store could be positioned as a subsidized public service similar to a water utility where customers pay a subsidized rate for a common good. Another potential benefit is that these stores could be more committed to remaining in the community as a long term anchor, as opposed to corporate stores that shut down without much regard for the impact on the community (such as the recent closures of Kroger stores in So Cal because of hazard pay requirements).”

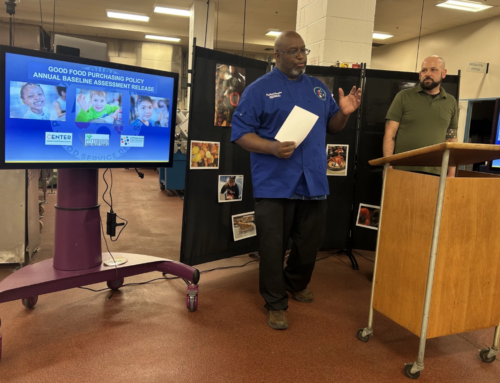

This would put City of Austin upstream in the context of food insecurity, but with more control over what ends up in the pantries of food insecure households and stronger relationships with food access focused NGO’s and community organizations and activists. Hence, it would be a move towards food sovereignty at the municipal level. The quality and sourcing standards should be consistent with Center for Good Food Purchasing (GFPP) standards that are being used at AISD in cooperation with the Austin Food Policy manager. This could create a tremendous pull in the supply chain for organic, regenerative, humanely-raised and worker-friendly products that would benefit many stakeholders in the economy and enhance ecosystems. And while there may be bureaucratic hurdles to overcome between the city and AISD, creating an additional supply network for the school system to tap into would be mutually beneficial for the food utility to have an additional outlet for inventory and demand planning of products.

In terms of governance, the city administration should do outreach to communities around the city to support and create visibility for this public food utility, particularly in the Eastern crescent, so there is shared dialogue and feedback on what is being stocked on a regular basis and how the utility is being used to eliminate food apartheid. The establishment of an oversight board or food utility commission is one way to go here, with community representatives being elected or selected to participate. The food utility should also prioritize hiring individuals from marginalized and impacted communities to ensure that the staffing and leadership of this infrastructure reflects the communities it is serving. That also goes for vendor contracts and supply chain, prioritizing Austin residents from Black and Hispanic/Latin communities that can own businesses that could supply products or materials to the utility on a contract basis, in additional other local and national vendors that meet the quality and sourcing standards. In terms of municipal operational management, I would suggest that creating a regional food system planning office through the food policy manager could be a start, while also creating this community engagement and accountability process.

Public food service as a commons:

Austin is one of the best food towns in the country, perhaps the world. The collapse and struggle of much of the restaurant and hospitality sector during Covid-19 has made us miss dining out, but has also been a painful economic burden to owners and workers. While the federal government has made some efforts to bail out the sector, it has not been commensurate with the need. The missing link here is a public sector investment in food service and hospitality that would tap the vast creative talent pool, experienced workforce and ample supply of amazing ingredients and connect the dots with the tremendous need to resolve hunger and food insecurity, particularly among younger residents and communities of color. The experience of Belo Horizonte, a city of 2.5 million residents in Brazil that has been working to eliminate hunger, should be instructive here. The city’s creation of a municipal food system planning department has been able to link farmers, nutrition experts and consumers through a variety of solutions, including the establishment of free public cafeterias. Using local, healthy and sustainable ingredients, the public cafeterias are popular and well attended. By not charging fees or establishing means testing, there is no stigma attached with stopping by and ordering a good, quick meal. Rich and poor alike enjoy the benefits, but it’s most crucial for folks without resources. And crucially, they are able to employ experienced chefs, line cooks, servers and other staff, something that our battered food service sector could surely use. While we may want to consider some modifications to this program, including, the size, location, menus and culinary focus, creating hospitality as a common good that provides good jobs, good meals and another income stream to local growers and producers, could be a strong sister project to the public food utility. It could also function as another physical space to revive and strengthen the live music scene as it returns. Such an institution may be another means of enabling good food for all and could add to Austin’s sterling reputation as a global foodie hub, but one now focused on justice and equity.

Invest in regional scale processing:

Less than 1% of the food consumed in Austin is grown locally. The amount of food consumed in Austin that is also processed and manufactured locally is unknown, but most likely also very small in proportion to the total. Yet, Austin has an admirable local farming community, as well as a thriving ecosystem of small scale food startups and growth companies that are producing a variety of products for the local and national market, from sauces, chips and salsas to frozen entrees and milled flours. These enterprises are fun and hip and tend to be affiliated with Naturally Austin and the progressive minded natural products sector of the food industry, of which I am a longtime member. However, there is not a stable local infrastructure for many mass market, basic food items that are sold in grocery stores, nor is there a middle ground of food industry infrastructure between our many local farms and the consumers at the end of the value chain. This infrastructure would include co-manufacturing, toll packing, and processing facilities for agricultural products that would add value, such as canning, aseptic or retort packaging, ultra-pasteurization, IQF (individually quick freezing), dehydration and milling, as well as facilities that could process and manufacture consumables such as snack chips, breakfast cereals or shelf stable baked goods like cookies, crackers or pastries. There is no scalable solution for preserving the annual summer bounty of tomatoes into jarred or canned sauces, and likewise the annual winter crop of greens does not have market outside of fresh sales.

When you consider that the farmers market sector is just over $1 Billion in annual sales and the grocery/Ecommerce sector is over $1 Trillion, it gives a sense of scale of the true nature of food consumption in this country. Processing is very much a necessary and egalitarian aspect of food consumption and should not be looked down upon by good food advocates or local food snobs. It is also where the vast majority of profits are to be had in the value chain, as consumer packaged goods companies regularly scale and sell for large multiples of their annual sales and profits.

Yet due to deindustrialization, industry consolidation and free trade agreements, much of the processing and manufacturing infrastructure is located out of state or out of the country. For example, most shelf stable store brand soups, beans and ready to eat meals for a number of the large grocery chains in Austin are processed out of state and even overseas. I know this for a fact because that was part of my job at Whole Foods, overseeing our private label assortment. And the co-packers we used were the same ones that our competitors used, just the product specs, ingredients and recipes differed. Locating more of such facilities in and around Austin could serve to not only create supply chains and inventory for such goods that could be sold locally or nationally in retailers, food service or even across town to the public food utilities, but could also create skilled, unionized, middle-class manufacturing jobs for many of the young poor and working class people in Austin that do not have a viable career path in the food industry outside of entry level food service or retail clerks, even if they have graduated from venerable, farm-skill focused programs at Urban Roots or Farmshare Austin.

A publicly owned manufacturing sector could also create revenue to partially fund the food utility program. Austin could create a one of a kind municipal-level manufacturing sector that could not only feed into the food security needs, but could also establish leadership in racial equity and food sovereignty by benefitting all members of the value chain, from farmers, workers, skilled engineers, food banks and consumers.

Technology and fulfillment for the public good:

Austin is a global hotspot for the tech sector and has a deep bench of experience, expertise and know-how. Due to the challenging geography, traffic patterns and public transportation infrastructure, getting food to the people may be the glue that binds the commons together in Austin. Creating a food commons app that acts as a public exchange where Austinites can upload their info, needs and locations can be triangulated with availability and location of delivery drivers or cyclists who could pick up goods from grocery stores, restaurants, food banks or public cafeterias for delivery, at no charge to users. App drivers or cooperatives could be contracted at living wages to create an additional public employment sector that competes with the digital sweatshop of typical delivery apps that service restaurants and grocery stores with extortionate rates and poor compensation to their gig workers. There is a growing network of platform coops and delivery coops around the world that are doing such work and Austin could be the first city to enshrine such work under the food commons umbrella. Such a sector could also generate income for the city by devoting a portion of the workforce to pickup and delivery for the private sector, for community members that have the means to pay a given delivery rate for groceries or meals that they buy. Based on the current market valuation of such private sector actors, there is ample demand for such services in the wake of Covid-19.

On a related note, I would also strong advise the city to invest in a dozen or so emergency snow plows and vehicles, as well as road salt and sand in case we get another freak snow event. I would also recommend that all such emergency food infrastructure be equipped with solar batteries and/or electricity generators, at least until our state grid is either properly regulated or hooked up to the rest of the country.

Conclusions:

These are a few of my ideas around preventing the collapse of local food systems during crises. While I have personally always been a bit of a “prepper” and making sure my family has enough food and resources to survive such a crises, that practice is useless without the community and public resources to support my neighbors. We need think in terms of public infrastructure preparedness for disaster and crisis, that could also act as a means of reducing hunger and food insecurity and a backstop to the energetic mutual aid projects underway, all while creating more public oversight and institutions in the food system. And such a plan would involve deep and extensive community outreach, engagement and leadership development. Good food, good jobs, good community feels like an Austin things. And Austin should take careful notice of the robust and extremely well thought out food policy planning in New York City that tackles many of these issues.

We have the impetus to create a more viable, transparent and sustainable food system that is accountable to the public interest, not subject to the fickle whims of the marketplace and resistant to the next wave of climate and public health shocks. Do we have any other choice?