This op-ed argues that our system of “cheap” industrial food and low-wage labor is incredibly costly in the long term.

What am I going to eat for lunch at school? What are my friends going to eat? Will they make fun of me for getting free lunch? Do I have enough money in my account? Is the lunch lady going to be nice? Will there be any healthy options? How’s the food going to taste? Will there even be any options for students like me who have allergies or dietary restrictions? I care about climate change and workers’ rights — is any of the food ethically produced? Students in the United States ask themselves these types of questions every day, but may feel disempowered and unsure about how to make change.

We need to organize a youth-led movement for school food justice. Universal free, healthy, tasty, eco-friendly, culturally appropriate school lunches could be a reality in the United States, but only if students, cafeteria workers (over 90% of whom are women), and communities join together in solidarity to fight for real food and real jobs in K-12 schools.

I’ve spent the last eight years interviewing cafeteria workers across the country and studying the history of school lunch activism. Along the way, I’ve learned what young people can do to make a difference, for themselves and for the millions of low-wage workers who grow, harvest, process, distribute, cook, and serve the meals they eat at school. I’ve been inspired by the vision for a Youth Food Bill of Rights put forward by Rooted in Community, a national network of youth-centered food justice organizations, and the efforts of nonprofit organizations like the Center for Good Food Purchasing and FoodCorps to create transparent, equitable, and sustainable food systems, beginning with school cafeterias.

I’ve also realized that school lunch is incredibly complex, including the federal, state, and local policies that dictate what individual cafeterias can serve and the supply chains that enable ingredients to move from farms, fisheries, and ranches to processing facilities and distribution warehouses before arriving in school kitchens. So let me take a step back and provide an overview of school lunch before digging into the question of how young people can organize for school food justice.

The National School Lunch Program (NSLP), which was established through the the 1946 National School Lunch Act and now feeds more than 30 million children daily, has a feminist history that dates back to the Progressive Era. At the turn of the 20th century, tens of thousands of women joined clubs, aid societies, and parent-teacher associations. They dreamed of serving lunches made with safe, nutritious ingredients free of cost to all children and providing both working-class and professional women with high-quality jobs in school food service. Some critics argued that free lunches were “socialist” and worried about the consequences of allowing working-class parents to offload the responsibility of caring for their children. The prevailing ideology of the time suggested that women’s care work should be cheap, if not free, even as more of this work shifted away from private homes into the public sphere. Yet these first-wave school lunch reformers managed to leave behind a national landscape dotted with hundreds of experimental models of nonprofit school lunch programs that later became the foundation for the NSLP. Later, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a coalition of anti-hunger and civil rights activists fought against structural racism within the NSLP, winning free school lunches for millions of poor children, mostly students of color from poor urban and rural communities.

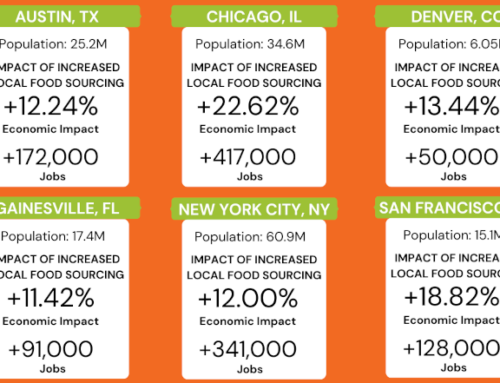

Today, the NSLP is a multibillion dollar federal program that provides lunches for free, reduced price, or full-price based on the income-level of students’ families. It operates in a political climate of austerity in which care is assigned little economic value. To keep financially afloat, school food service directors often rely on a system of “cheap” industrial food and low-wage labor that is incredibly costly in the long term, to individuals and society at large. Purchasing local food from small- and medium-sized farms through farm-to-school programs, removing “ingredients of concern,” e.g., artificial colors, flavors, and other additives, from school lunch supply chains, incorporating a greater percentage of healthy, climate-friendly ingredients into school meals, expanding access to free lunches using the Community Eligibility Provision, outlawing “lunch shaming,” and organizing cafeteria workers to fight for real food and real jobs are just some of the strategies activists are using to address the various forms of injustice within the current NSLP.

Youth can and should play a key role in transforming not only school lunch, but also the economic and ecological systems they will inherit as adults. There are many ways to take direct action:

- Start by talking to others about your own experiences with school lunch and the issues you care about. Educate yourselves so that you can connect your individual school lunch concerns with larger issues like racial justice, economic justice, climate justice, health equity, and gender equity. Soul Fire Farm’s curriculum is useful for learning about food justice in general, and the Labor of Lunch curriculum guide is specifically tailored to the NSLP.

- Check out these tips for youth leaders looking to organize and build power in their communities. Learn from and connect with others in the school food justice movement, like the students in San Diego who fought to replace factory-farmed chicken with Halal chicken, and the students in Philadelphia who organized to win healthier menu items and water bottle-filling stations. Share your experiences on social media using #schoolfoodjustice.

- Start small and build your base, then look for wins at different levels: What can you accomplish in your school building? Districtwide? Nationwide? Consider connecting with national initiatives such as the Good Food Purchasing Program and the Real Meals Campaign.

- Ask your family to get involved. The Chef Ann Foundation has a fantastic parent advocacy tool kit and FoodCorps has an excellent policy action center with an option to sign up for policy alerts.

- Become a FoodCorps service member and get paid to organize for school food justice. Applications are accepted on a rolling basis, and you must meet the eligibility criteria to apply. Another great way to get paid to make a difference is to apply to work in a school kitchen or cafeteria.

- Remember that the “lunch ladies” aren’t your enemies; potentially, they’re some of your strongest allies. Support their labor struggles whenever possible and pressure your school board to invest in school-community kitchens, scratch cooking, and quality jobs for cafeteria workers.

- A new bill, introduced by Vermont senator Bernie Sanders and Minnesota representative Ilhan Omar, would provide free universal meals to all children, wipe out school lunch debt, increase the amount of money schools receive to cover the cost of preparing meals, and incentivize schools to purchase local food. Encourage your elected officials to support this legislation, and host events to educate voters about what enacting the bill would mean for you and your community.