Jose Oliva is the codirector of the Food Chain Workers Alliance, which aims to improve wages and working conditions for “all workers across the food chain.” The FCWA recently helped develop a Good Food Purchasing Policy, a set of standards that emphasizes local economies, sustainable production, fair treatment of workers, animal welfare, and nutrition. These standards have been adopted in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Oakland. Oliva lives in Chicago.

How did you get interested in the connections between food, justice, and workers’ rights?

My family are refugees from Guatemala. After arriving in the United States, my family and a few other families started an organization called Casa Guatemala for mutual support. I was a volunteer in the organization.

One day in 1999, a woman in Chicago contacted Casa to say that her husband had been kidnapped. I assumed she was talking about her husband in Guatemala. But she said no, he had been kidnapped in Chicago. She said that he was a day laborer at la parada and someone picked him up for a job, but he never came home. I felt like she was speaking Greek. I didn’t know what la parada was, and I didn’t know what a day laborer was.

What is la parada?

It’s the name for a street corner in Chicago where day laborers gather in the morning in hopes that an employer will offer them a job for that day.

What happened in that case?

We ended up working closely with the Chicago Interfaith Committee on Worker Issues—it is now called ARISE Chicago—and with the Civil Rights Division of the FBI. They found out that there was one guy that everyone called “the Chino” who would pick people up from the street corner and then sell them to a series of restaurants. The FBI staked out the restaurant and busted the whole ring.

For me, it was an important moment. I felt like I had inadvertently picked up a rock and now I could see all the little grubs underneath. I saw an underground economy, and I found it almost unbelievable that there were folks willing to engage in criminal activity to this degree in the United States. But it also became clear to me that this was not an isolated incident.

What are the conditions of this underground economy?

Labor has become more commodified: you sell a specific unit of labor. Instead of working 40 hours for one employer who pays your health-care insurance and gives you some benefits, you might be an Uber driver or work in three restaurants.

Have you seen this economy close up?

I worked in the restaurant industry the whole time I was in college. Guatemalan refugees who came in the 1980s were not granted political asylum. The State Department denied that anything was happening in Guatemala that made people need asylum.

I was undocumented for 24 years. I went to high school, but once I graduated I couldn’t go to a four-year university, because I couldn’t get scholarships or grants. Eventually I finished my degree by working at restaurants and paying for credit hours as I went. That gave me a worm’s eye view.

When I began to organize with the Interfaith Committee, it wasn’t just an intellectual interest. I had worked in the industry. I knew what it was like to be exploited.

Workers face a particular challenge in this fragmented, underground economy. What do you see as the future for unions in this context?

I don’t think we yet know fully how to intervene in this economy. There are new modes of production and new populations of workers—immigrants and women. Whereas at the start of the 20th century, there was a vast consolidation of workers into huge factories, today the workforce is atomized, with Uber drivers and bike messengers as examples.

But just as craft unions didn’t go away when industrial unions formed, I don’t think you will see the end of unions. But we are going to need new forms of collective bargaining. There are things like online forums where, for example, Uber drivers can all get together. That fosters thinking that we can talk and work together even if we are not in the same place. There is an increased role for coalitions over all. And this is the place where faith groups and community groups are central to coalition building.

How did this work lead you to the Restaurant Opportunities Center?

After the incident with the day laborer, I started working for the Restaurant Opportunities Centers. It was a place where I felt I could see the bigger picture.

ROC was born out of the attacks of September 11. Seventy-three workers died at the World Trade Center in a restaurant called Windows on the World. The rest of the workers there founded ROC as a tribute to those 73, vowing that they would make the restaurant industry better.

We noticed at ROC that there is a growing awareness of food and food systems at every level of society. Some people are concerned about what food does to the human body; some are concerned about what food does to the environment; others focus on how food and food access affects communities. But nobody was talking about the workers in all this—the people who actually produce, transport, sell, and serve food.

How many workers are we talking about?

There are over 20 million workers in the food system. It is the largest private sector employer in the United States. It’s bigger than health care.

These workers are the lowest-paid in the country, and none of them has a clear ladder for improving their conditions.

This system of workers needs a unified organization. It can’t be restaurant workers over here and farmworkers over there and meat and poultry processors in another place. We needed to bring all of those sectors together into one coalition. That’s what led to the creation of the Food Chain Workers Alliance in 2008.

What’s its mission?

When we started the alliance, our mandate was to insert workers into this discourse about food. At first we urged people who were working on food issues to talk about workers. But then we realized the truth of the African proverb: “Anything about us without us isn’t for us.”

Now we are making workers themselves a part of the conversation. Consider the issue of food waste. Food waste is the third-largest source of carbon emissions on earth. Workers and working conditions need to be part of this conversation—and now they are, thanks, in part at least, to our efforts.

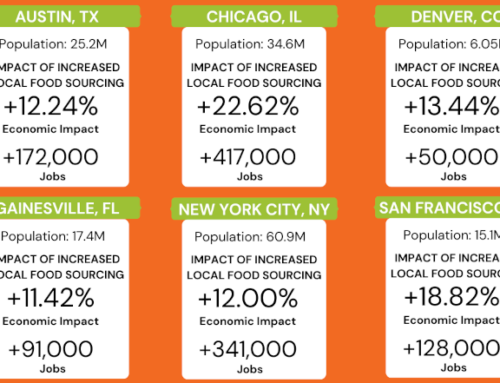

We also wanted to create a tool that would help organizations, municipalities, and other entities connect the dots of the food system. It took us a long time to think how to do this. Eventually we landed on the Good Food Purchasing Policy, which sets standards in five categories: environmental sustainability, worker fairness, animal welfare, local economies, and health. Each of these values is weighted equally. By these standards, it’s not enough for a company to have great environmental practices; it also needs to treat workers fairly.

After being adopted by the city of Los Angeles in 2012, the GFPP was adopted by the LA Unified School District, which serves 650,000 meals a day. Now the district has to consider all five of these values when they purchase food. Before the only criteria was it had to be the cheapest.

What is your ultimate goal with the Good Food Purchasing Policy?

We want a food procurement process in every city in the United States that requires companies to change their practices. The movement is about increasing the good rather than penalizing the bad.

Have you seen any evidence that companies’ practices are changing to meet the standards?

In LA, there was a very strenuous process with the poultry producer Tyson. The school district was convinced that Tyson was the only company that could supply the huge quantity of chicken that it needed. But Tyson was unable or maybe unwilling to turn over its books to the Center for Good Food Purchasing (goodfoodcities.org), the third-party verifier and the central hub for the national work. Tyson kept lobbying for an exception. The school district held its ground, because GFPP was the law.

What kind of information from companies is needed?

We need to know if Tyson plants have OSHA violations and other labor and employment law violations; we need to know where the chicken being supplied comes from and how is it transported. Because it was unwilling to answer those questions, Tyson is no longer one of the providers of chicken to the LA Unified School District, which was their second-largest contract. GFPP is now implemented in San Francisco and Oakland as well, and we are close to reaching agreements in Chicago, Cincinnati, and New York.